by Gerald W. Schlabach, University of St. Thomas

Mennonite Catholic Theological Conference

University of Notre Dame

31 July 2007

session: “Toward a Healing of Memories”

English teachers and editors tell us not to mix metaphors. Well, it’s a good thing Jesus got to us before they did. To project the Kingdom of God or to explain God’s love for the lost, Jesus unabashedly gave us multiple metaphors and parables. A mustard seed, yeast, a treasure hidden in a field. A lost coin, a lost sheep, a prodigal son. For the mystery of God’s work, we seem positively to require mixed metaphors. Our job is to collate them and gain a fuller picture by connecting their dots.

Part three of Called Together to be Peacemakers offers us, with its very title, one metaphor for our most basic of ecumenical tasks, “the healing of memories.” “Bridgefolk,” the name of the grassroots organization for dialogue and unity between Mennonites and Roman Catholics, offers another image, the bridging of peoples. I would like to collate these two images by exploring yet another image — scars, and the function they play in the healing of actual bodies, wherever the painful separation of flesh has occurred.

In a faith so incarnational as Christianity, the healing of memories in the broken body of Christ will remain merely gnostic if it is not enfleshed through the bridging of folk.[1] And when severed flesh comes together, scars are the bridge, while scar formation is a sign of returning health. Yet even in the healthiest of recovering bodies, scars remain.

And scars remind. Even when memories heal, in other words, the body writes new memories onto its very flesh. Often such scars continue to itch. For some, this can be a calling, to incarnate the healing of memories, to be the scars that close gaping wounds in the body of Christ, and frankly to itch.

Bridge people, I argue, ought neither to be nor be seen as distractions in an otherwise clean bilateral process of ecumenical dialogue. Nor should their “double belonging” be taken merely as the product of post-modern messiness. To be sure, something can be unsettling about both still-forming scars and folks who remain “on a journey.” But in the incarnational faith we call Christianity, no healing of memories will be complete — or really even begin — without someone there to enflesh the rejoining of separated parts.

Bridging

Almost every year, someone participating in a Bridgefolk conference either plays with the image of a bridge or asks whether the metaphor really works. Bridgefolk began in the late 1990s as Ivan Kauffman and I began to wonder if we were in the presence of a nascent, still-inchoate, movement. Through friendship and word of mouth we were learning of a striking number of Mennonites drawn to Catholic liturgical or contemplative traditions, and of Catholics drawn to Mennonite traditions of service and peacemaking. Hoping to figure out what was going on, we soon invited MarleneKropf and Weldon Nisly to join us in planning an unadvertised retreat bringing together 25 Catholics and Mennonites to tell their stories, pray and discern. More as an act of generic description than one of poetry or theology, we simply called it a bridging retreat.

So what sort of bridge is this?, someone wonders. Yes, a few of the folk in Bridgefolk have “crossed-over,” changing their primary ecclesial identity from one church to the other. Yet those of us who have done so are not the sort of “converts” who are burning their bridges by renouncing the values or legitimacy of the church communities that formed them. In any case, far more often, ours is a bridge that facilitates hospitality and exchange, allowing once-estranged Christians in these two traditions to meet as friends, find inspiration in one another’s charisms, learn from one another’s practices, but then return home, back across the bridge, enriched.

If the first bridging metaphor — crossing over — is too triumphalistic, however, the second — amiable exchange — may be too benign. For it fails to account for either the pain or the joy that many of the folk in Bridgefolk have experienced. On the one hand, some have felt at times like homeless refugees no longer fully at home in either tradition, grateful to find shelter under the Bridgefolk bridge, yet painfully aware that such a home can only be makeshift and provisional at best. On the other hand, some of us are interchurch couples or individuals with dual membership, trying to find creative, comfortable ways actually to live on the bridge. Bridges aren’t supposed to become the site for permanent homes, right? Except that in rare cases they do — as with the charming PonteVecchio in Florence.

Still, the last thing we in Bridgefolk leadership want to imply is that ours is an actual church home. A home away from home — maybe. An ecclesial movement, as Rome approvingly labels certain kinds of groups — gladly. But not a church. And only even a bridge between our churches so long as few better options exist for being simultaneously Mennonite and Catholic. Thus the common prayer that has been our one shared “rule of life” since 2001 actually does not speak at all of a bridge between Catholics and Mennonites. Rather it speaks of a bridge to somewhere that neither Christian community is currently fully at — a bridge to God’s “coming Kingdom,” a bridge “to that future of unity and peace which You ever yearn to give to your Church, yet ever give in earnest through Your Church as You set a table before us….” Gratefully we later learned that both Cardinal Walter Kasper, head of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, and then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict, have named exactly this to be the proper goal of ecumenism — not that long-separated Christians move closer to one another but that together we grow closer to Christ.[2] What exactly the far end of that bridge will look like thus remains to be discovered.

Healing

I do not know whether even my closest friends or colleagues have noticed. But every once in a while, in moments of distraction, I reach across my chest and scratch an itch. Nine years ago, I had surgery to remove a lymph node that had become impacted with the infection from cat scratch disease. I will spare you the gorier details, but this much seems necessary: The wound that surgery leaves in a case like this cannot simply be closed and sutured. It must remain open to be regularly cleaned and dressed until it heals and closes from the inside, lest a new and far more systemic infection occur. Healing cannot be rushed. The wound requires patient, loving attention, in my case at the hands of my long-suffering wife. And then, as with any scar tissue, an itch may persist, even after healing is complete, as I can attest.

That scars abide in the body of Christ, even where healing occurs, should not surprise us. Christianity is a faith of realistic hope not cheery optimism. At its very center, after all, is a gruesome cross that we not only must behold, but recognize as our own doing. It is precisely because we can look into the face of suffering and shame that we find the courage to believe, in the words of Julian of Norwich, that “all will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.” After all, even the resurrected body of Jesus continues to bear the visible wounds of suffering (John 20:27).

Scars function in at least three ways. I have already mentioned the first: Scars are the place where the body’s separated flesh comes together. In ways small yet nonetheless decisive for the health of the whole, they bridge. Second, scars are places that mark the eschatological “already” and “not yet” of our own resurrected bodies and — more to the point — of the perfectly healed, reunited, resurrected body of Christ. If even in resurrection, scars may still be visible, then those scars that continue to ache in the still-healing body of Christ are a sure reminder of the Church’s “not yet.” Yet even so, even now, we may celebrate an “already.” The grace that is the wonder of the human body is capable of amazing healing, even in the meantime.

Third and finally, scars are a place that functions to set an agenda for the body. Scars in the process of healing marshal energy and resources from throughout the body at those locales whose recovery is critical for the well-being of the whole. And even after healing is complete, scars want to be scratched. They incite other parts of the body to pay attention. They itch. So that even as the body of Christ heals its memories, the scars that remain also continue to provoke memory, itching and calling for further action.

To illustrate the healing-yet-still-itching role of Catholic and Anabaptist-Mennonite bridge people in the body of Christ, I would like to share an imagined conversation. Let me defer for now the question of whether and where such a conversation might actually take place.

To make the conversation easy to follow, I will call the Mennonite Anna B. and the Catholic Cathy. Anna is a deacon in her local congregation and is pursuing a master’s degree in spiritual direction. Cathy works full time as social justice coordinator in her local parish. They have been friends for a number of years, and when Called Together to be Peacemakers came out they initiated a study of the document, bringing together members of both communities. The study is just about to wrap up and they are meeting at a coffee shop to debrief and discuss what to do next.

“Hey, I thought our last session on the healing of memories went well,” says Anna as they sit down at a corner table. “What a relief!”

“That we’re done?” asks Cathy with surprise. “I’m going to miss meet—”

“No, not that. What a relief that we really are both Christians! The document says so! Mennonites and Catholics are allowed to see one another as brothers and sisters in Christ [¶ 210].”

Catching on, Cathy chuckles. “Of course you and I knew that already. It’s a shame that it took our high-level delegations five years to reach the same conclusion!”

“Or five hundred years,” Anna interrupts.

“Yeah, I know,” agrees Cathy. “I’m just sort of teasing them in absentia. They did have a lot of issues to work through. Still do, I guess. But at least we’re moving beyond mutual condemnation, as Cardinal Kasper put it [¶ 202]. They really came a long way in facing ‘those difficult events of the past.’ I mean, most of us Catholics don’t even know that we used to persecute groups like the Mennonites. I didn’t, and I work on human rights issues! I can really understand what they mean by ‘the healing of memories.'”

“Or ‘purification of memories,'” suggests Anna.

“Whatever. The document uses the terms interchangeably, doesn’t it?”

“No, not whatever,” Anna insists. “I’ve been thinking some more about this since our last meeting. I don’t think they’re quite the same. It’s one thing to clear up a misunderstanding. That’s purification. It’s like cleaning a wound. But that doesn’t mean the wound is healed yet. Especially” — Anna’s voice grows quieter — “when the wound gets reopened every once in a while.”

Cathy is a bit taken aback: “What do you mean?”

“Well, it’s hard enough to face difficult events of the past, but what about events of the present?”

“I’m not sure I follow you,” says Cathy, still puzzled. “Persecution is long past. Vatican II committed Catholics to the principle of religious liberty. We discussed all this, you know. And the Catholic Church’s growing commitment to peace and nonviolence — I wish it were happening faster, but it is happening!”

“Not at the table,” says Anna, with more resignation than bitterness. “Suddenly at the last minute I’m not seen as a sister in Christ after all. Or if I am, I’m second class.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. That. Of course,” says Cathy. “You know how torn I feel about that. You’re welcome to participate in the Eucharist as far as I’m concerned. But, well, I’m just not the only one concerned. You know me. I get as frustrated as anyone that change takes so long in the Roman church. But that’s part of what it means to be a Catholic — to move together as a worldwide body. So the Eucharist isn’t only about you, me, and Jesus. It’s also our fullest expression of visible church unity, so where unity is incomplete, well, I suppose it’s better to be honest. I mean…. Geez, I can’t believe I’m defending the rules! Maybe it feels different to me because we Catholics are so good at finding exceptions to rules. I’m sorry if I was insensitive.”

“It’s okay,” Anna assures her friend. “On one level, I get it too. You know how much I’ve come to love the liturgy. When I attend other Protestant services now and they have open communion, sometimes it feels a little too cheap and nonchalant. Even at my own Mennonite congregation, we’ve finally agreed to celebrate the Lord’s Supper once a month, but one time we do it one way, then next time another way. So I’m torn too. If it weren’t for the thorn of your all-male priesthood, I could almost start to appreciate your rules!”

“Their all-male priesthood,” Cathy interjects, and they both laugh.

“So as I was saying, it’s okay. I get it. I guess.”

“Well, that wasn’t very convincing,” Cathy notes.

Anna pauses, trying to decide whether it is worth the risk of going on. “I get it — until we get to that one line: ‘Happy are those who are called to this supper.’ You welcome me as a friend and sister. The liturgy, it … I guess I would say it enfolds me. But then at the last minute, am I called to this supper or not? Am I a sister in Christ or not? All I know is that I’m not quite ‘happy’ at this supper. In the very moment of welcome I’m turned away because I’m a second-class Christian. It isn’t even enough that I sincerely pray the next line: ‘I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.’ Jesus can say the healing word but I’m not worthy just because I’m not a Catholic?”

“Well,” says Cathy, “here’s where I’m the one who sort of gets it and sort of doesn’t.” She hesitates, then stammers: “You could… I mean… Look, we’ve had this study group for nine months without anyone trying to convert anyone else, and I’m not starting now. But if the Eucharist is coming to mean so much to you, you could become Catholic. I’m not saying you should, y’know. It’s just that, well, I don’t think it’s quite fair to say that the church is turning you away.”

“Oh come on, you know why I can’t do that,” says Anna. “You’ve told me your own frustrations as a woman working within the structures of the church. Do you really think you’d join if you weren’t a ‘cradle Catholic?’ You say the church is moving toward a stronger commitment to peace and nonviolence, but only slowly. Do you really expect it to give up its just war teaching — ever?

“Don’t worry that you’ve stepped over the line; I appreciate your honesty. But I have to be honest too: I just don’t know how I could be part of a church like that. Still too Constantinian. Still way too patriarchal ….

“… Still the whore of Babylon?” Cathy interrupts.

“No, I didn’t say that!”

“But you did say that the Roman Catholic Church still hasn’t changed enough, is still not good enough. Not worthy. Isn’t that just a politer way of saying what Protestants have been saying for almost 500 years?”

Both friends are silent for a minute. At last Anna finds a way to connect her thoughts and feelings with those of her friend: “Well, it’s tricky, this business of worthiness and recognition. I guess both our churches find ways to turn each other away at the last minute.”

“‘But only say the word…”

“…and I shall be healed.”

“At least we have this table.”

“Yeah — want some more coffee? I don’t think our work is over yet!”

So could some version of this conversation actually take place? In the hall outside this meeting? In the cafeteria at our Bridgefolk gatherings? On the tearful late-night bed of a Mennonite-Catholic marriage?

No and yes. I have been in all of these places, marveling both at growing trust among friends and sudden breakthroughs of insightful candor. But I have yet to hear a conversation quite this blunt. Except for one place — my own Mennonite Catholic head. There, I hear it often. And though I can’t know for sure, I suspect that versions of this conversation replay regularly in the minds and hearts of others who have found some sort of way to be simultaneously Mennonite and Catholic. The conversations are not just intellectual matters either — much less gnostic — for they take on their poignancy and depth precisely because we are keeping our bodies planted in both communities, continuing to serve and be present rather than leaving one for the other. The pain of estrangement we once felt may have abated. But an itch lingers on. If we are scar tissue in the body of Christ, that itch keeps us longing and working for less painful, ever healthier ways to bring together divided flesh in the body of Christ.

Dialogue

So I am arguing that bridge people play a critical role in the ecumenical healing of divisions. I am seeking to name spaces within the ecumenical movement where grassroots dialogue can and does play a role. I will close by envisioning some possible next ways in which Mennonites and Catholics acting together can contribute to Christian unity in fresh and creative ways. These arguments inevitably imply that ecumenical dialogue and progress will suffer from certain limitations if they only proceed through high-level encounters, and I mean to explicate some of these limitations shortly. But let me be clear: none of this aims to detract in any way from the immense gratitude that grassroots bridge people owe to the classical ecumenical movement functioning on more official levels.

A first affirmation: Historically, the impulse for ecumenical endeavors has sprung from what matters most — missio Dei, God’s own outreach to the needy world that God loves, and the call of God’s Church to participate in this mission. As it took shape among Protestants in the early 20th century, the classical ecumenical movement was virtually indistinguishable from the missionary movement then in its heyday. The disunity of churches obstructed a clear presentation of the gospel, after all, and young churches that did form in new regions of the world often found North Atlantic denominational structures a confusing puzzle at best.

Later, when the Catholic Church made its decisive commitment to ecumenical dialogue at the Second Vatican Council, that context was no mere coincidence. The larger purpose of the council was to reinvigorate the church so that it might better communicate the gospel in the modern world.[3] As he opened the council Pope John XXIII expressed his hope that it was “bringing together the Church’s best energies” to prepare the church to proclaim “more favourably the good tidings of salvation.”[4]

For their part, Mennonites have discovered an ecumenical mandate precisely as they have engaged in mission and service around the world. Integral to the corporate culture of the relief, development, and peacebuilding organization Mennonite Central Committee, for example, is a commitment to “work with the church” whenever possible in any given region or locale. But since this can hardly involve Mennonite partners alone (given the relatively small size of the worldwide Mennonite communion) MCC has in practice inculcated a strikingly catholic ecclesiology — far more than Anabaptist-Mennonite theology has quite known how to name.

A second affirmation unfolds to become multiple affirmations: We can be grateful for a diversity of charisms among multiple ecumenical dialogues and do not need to celebrate one at the expense of others. Naturally, each dialogue takes on the character and primary concerns of its respective dialogue partners. The international dialogue between Mennonites and Catholics took up a number of issues but two or three were particularly urgent for the relationship between these two communities — the memory of sixteenth-century persecution, the contemporary call to peacemaking, and (extending from both) the relation of church and state, both historically and today. It is not that other matters are unimportant.[5] Yet obviously we cannot take on every issue at once. That every dialogue has its own charism is thus a great gift. Mennonites and Catholics in dialogue together are freer to drill down into their own matters of urgency knowing that others with the concern and competence to focus on different issues are doing so.[6] So in the diversity of ecumenical charisms, we owe great debts to one another; each frees others to pursue their respective callings.

While gratefully acknowledging the legacy of classical ecumenism, however, we must honestly name certain limitations. The “we” here refers especially to those who come from, or are sensitive to, the so-called Free Church tradition.[7] As the late John Howard Yoder persistently argued throughout his career, however generous particular ecumenists have hoped to be, the very structure of ecumenical dialogue has too often served to marginalize the free churches.[8] Arguably, any assumption that high-level negotiators representing their churches might deliver blocks of Christians into new configurations is covertly Constantinian at worst or question-begging at best.[9] If free churches instead understand church authority to proceed “from below” — or better, from Christ “above” who distributes a wide diversity gifts among all believers[10] — then the very shape of the ecumenical table dare not preclude their full participation.

Even when heirs to the Radical Reformation have found a place at the ecumenical table, Yoder also reminded us, the classical agenda encoded in the formula of “Faith and Order,” has tended to assume that matters of doctrine and church structure were “confessional issues” and their resolution what is most essential for greater church unity, but that ethics and discipleship are secondary.[11]Thankfully, ecumenists are increasingly recognizing that the heirs of the Radical Reformation have a rightful claim to the argument that these too are “confessional” matters. If Yoder were alive, however, he would still be pressing the question of whether their full recognition does not require a more radically thoroughgoing review of the Faith and Order agenda itself — a reshaping of the table, as it were.

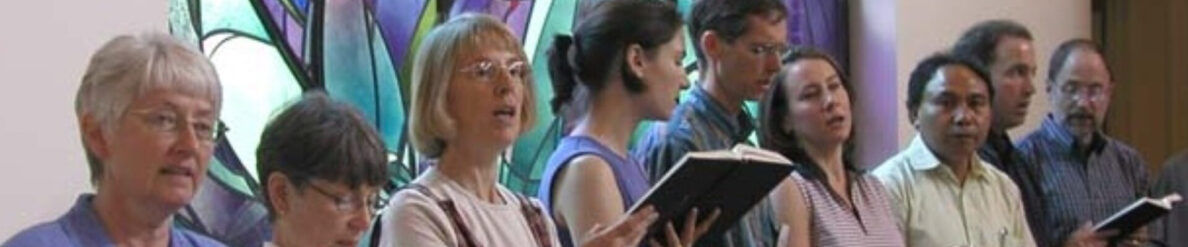

The experience of Bridgefolk suggests at least two other limitations to classical ecumenism. First, it has not accounted very well for post-modern fluidity of identity, and is only beginning to do so now. The standard agenda of ecumenical dialogue has taken up matters of doctrine and polity with a certain assumption that long-standing historical positions continue to have purchase in the respective Christian communities. Far be it from me as a professional theologian to suggest otherwise; one of our perennial tasks as theology professors is to convince undergraduates that ideas of centuries past continue to shape our lives. But let’s be honest: This very pedagogical task is more urgent than ever precisely because students and parishioners alike feel unprecedented freedom to mix and match, try on a succession of identities, and forge patterns of double belonging. The obvious danger here is an individualistic “cafeteria Christianity.” Yet leading ecumenists themselves imply gratitude for the larger possibilities that the post-modern condition opens up, whenever they recognize the power of “spiritual ecumenism” — the way that formally divided Christians overcome old suspicions and develop mutual appreciation whenever they work together for the common good, pray common prayers, sing together, and so on. Though ecumenists may celebrate spiritual ecumenism more than they bemoan cafeteria Christianity, what all of us have trouble accounting for is how we can have one without the other. The fluidity of post-modern identity seems both to lubricate ecumenical conversation and to allow people to slide over hard questions that will haunt us later if we hope to move any closer to full communion.

Which brings me to a final limitation. If our only hope and model of ecumenical progress is a painstakingly negotiated solution to every church-dividing issue between every estranged Christian community, then the ecumenical horizon will ever recede. Patience is a key Christian virtue, of course, and eschatological tension is good theology. But a Christian has only one lifetime to live out his or her earthly vocation and live into the path of discipleship Christ has placed before us. Perhaps some of us have succumbed to the vice of impatience and are trying to hurry the eschaton. But when we find that full participation in the sacraments and ample communion with Christians through the ages and around the globe is necessary to sustain lives of nonviolent discipleship — in other words and for example, when we find our Christian identities already taking on both a Catholic and a Mennonite shape — then forgive us our itches, but we wonder how long we must wait for a not yet that seems more tragically unnecessary than properly eschatological. Our plea is not for premature solutions to the serious issues that Christians must face after centuries of division and mistrust. Our plea is to concentrate on moving together toward Christ rather negotiating our way toward each other. Concretely our plea is for fresh models aiming not so much to resolve historic differences as to transcend them.[12]

Vision

A reshaped table, hosting a search for fresh models, must somehow make a place for the lessons of grassroots ecumenical dialogue and the voice of bridge people who may not represent one church or another officially, but who bear in their own bodies the healing scars of their struggles for reconciliation. As my brief review of Yoder has already implied, learning to accommodate messy grassroots modes of discernment and decisionmaking will be critical for any dialogue that includes the Free Church tradition, anyway. One can understand the puzzle someone like Cardinal Kasper faces when he surveys the exponential expansion of “evangelical, charismatic and above all Pentecostal communities,” when he recognizes that the horizon of church unity will only recede further if older churches cannot find ways to converse with these new ones, but when he also finds it nearly impossible to identify representatives of these communities who hold corresponding decisionmaking positions that allow them to serve as conversation partners.[13] Yet the puzzle underscores the need. And fortunately, learning to converse with a nonhierarchical world communion such as the Mennonites offers practice for talking with other groups, whose dynamics are more akin to the Radical Reformation than the magisterial Reformation.

What may not be so obvious is that it is eminently appropriate for a group like Bridgefolk to emerge in the context of ecumenical conversation involving Mennonites. Mennonite ecclesiology expects discernment to take place throughout the gathered body according to the model of 1 Corinthians 14, whereby even the words of the most gifted leader must be tested by the local assembly. When Catholics are attracted to Mennonites, one of the draws is sometimes this participatory pattern of church life. Thus, if Bridgefolk did not exist, it would probably have to be invented.

Here though we must cross-reference another major challenge that Cardinal Kasper has identified in the current ecumenical landscape. Kasper notes that the ecumenical scene is simultaneously fragmenting and reconnecting through new kinds of ecclesial networks and unpredictable new forms. Uncertain whether it is proper for the pontifical council he heads to enter into dialogue with these energetic yet unofficial groups, Kasper nonetheless voices gratitude for their commitment and seems intrigued that they come knocking.[14]

The challenge Kasper is identifying as he paints this picture is one that others associate with postmodernity. It is the phenomenon that paradoxically couples greater awareness of the role of traditions and community identity with greater fluidity of identities. The postmodern condition brings many dangers, of course. Elsewhere I have argued that too often it is little more than a pose for a kind of hypermodernity;[15] identities found and shaped in this way are too easily gnostic, individualistic, and unaccountable to any real and stable community. And yet we must have the courage to recognize opportunity here too.

Postmodernity has loosened rigid identity configurations that long kept peoples, cultures, and churches distrustful, estranged, and unable to exchange gifts. Postmodernity has thus allowed for fresh, creative, once-unthinkable conversations. It is reshaping our identities whether we welcome its changes or not. For those who welcome its opportunities self-critically, it makes once unthinkable identity configurations possible. Ivan Kauffman frees us from obsessing over whether postmodernity is simply producing “cafeteria Christians” when he proposes that the postmodern age is actually misnamed. At least for Christians, our age is in fact the “ecumenical age,” says Kauffman. For the realization is dawning: Everyone needs the gifts that everyone else has to offer.

Still, how to have the benefits of our postmodern (a.k.a. ecumenical) age while minimizing its dangers? My appeal is to church officials and in its essence it is really quite simple: Give bridge people better ways to be accountable; help them make “double belonging” into something more than their own improvised idiosyncrasies.

Though no fully canonical model yet exists for double belonging to both the Roman Catholic Church and some other Christian communion, models and categories do already exist. Some are the precedents of centuries, in fact, while others have only recently emerged.

Already before anyone had begun to imagine such a thing as a “Catholic Mennonite” or “Mennonite Catholic” identity certain hybrid categories existed in both traditions — ecclesial models and patterns that defy easy pigeonholing according to a Troeltschian typology of “church” and “sect,” or that otherwise allowed for “double belonging” long before anyone had coined the term.

- On the one hand, monasteries and religious orders had long embodied dynamics within the big tent of Catholic Christendom that contemporary “believers churches” see as essential for authentic Christianity — mature adult commitment, thoroughgoing discipleship, both taking primary shape in accountably local Christian communities.

- On the other hand, when Radical Reformation communities emerged, critics from the magisterial Reformation intriguingly wrote them off as married monastics. Later historians have seconded the observation. Rather than resist the designation, some of us now embrace it as a reminder of Anabaptism’s Catholic roots.

- For centuries, recognition of alternative rites has been one way for the Roman church to maintain or restore communion with local churches whose histories have followed a divergent trajectory, resulting in non-Roman liturgies and polities that can nonetheless claim ancient precedent.

- Another kind of hybrid polity began to emerge in Latin America already prior to Vatican II — base ecclesial communities drawing together small groups led by lay leaders the church itself had trained. Though base communities have sometimes suffered from political struggle in both society and the church, leaving them with a tarnished reputation among conservative prelates, we do well to recall that base communities began as the bishops’ own solution to some of their pastoral challenges.

- Meanwhile and with little controversy, Mennonites in North America have sometimes resolved pastoral problems resulting from their own history of division by allowing congregations to affiliate with more than one denomination. In a few cases, the second (or third!) affiliation has not even been Mennonite.

- And overseas, Mennonite mission agencies have won recognition as leaders in their willingness to work with African independent churches and others without any expectation of denominational affiliation. Add to this the many examples of MCC collaboration with Catholic bodies in Latin America, the Philippines, etc., and the result is a striking range of creative affiliations across the continuum running from “low” to “high church.”

Still other models have been emerging in ways that seem to respond even more obviously to postmodern pastoral needs and dynamics. Not surprisingly, all of them have figured into the journeys of at least a few of the folk in Bridgefolk:

- One way that some Mennonites (and many other non-Catholics, of course) have found to connect with Catholic traditions has been as Benedictine oblates and through similar “third order” affiliations.

- Though not well known in North America, the Vatican has been looking to “ecclesial movements” to play a leading role in the revitalization of Christianity especially in Europe. The theological tendencies of ecclesial movements cover a broad range of Catholicism, from traditionalist Opus Dei, to ecumenically generous Focolare, to socially activist Sant’Egidio. The polity of ecclesial movements is hybrid not only because they are emphatically lay-led, but in some cases because they admit non-Catholics into their membership.

- Although formal recognition of non-Roman rites is reserved for traditions with a claim to ancient precedent and apostolic continuity, a case can be made that at least one community and its liturgy has received informal or de facto recognition as a rite — the Taizé community centered in France. Founded by French Protestants soon after World War II in order to promote and embody Christian unity, Taizé has developed its own interchurch liturgy, and enjoyed warm relations with the Vatican. At the funeral of Pope John Paul II, officiating Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger — soon to be Pope Benedict XVI — offered Taizé’s aging leader Brother Roger the Eucharist while the world’s cameras rolled. At Brother Roger’s own funeral a few months later, Cardinal Kasper officiated. In a church that is highly attuned to ritual meaning, and that prefers to let policy and doctrinal development settle through received practice before ratifying them through canonical pronouncement, surely these were quite deliberate signals.

- Such historic developments still can take decades to play out, so individuals who seek to identify with one tradition without renouncing their formative tradition must continue to improvise. A few have in fact made formal dual affiliations. In my own case, for example, I was confirmed in the Catholic Church at Pentecost 2004 but have maintained associate membership in a Mennonite congregation as well. In Bridgefolk we are aware of at least a half dozen people who have worked out similar patterns. Crucially, they have often done so with the knowledge, support, or even the encouragement of both congregational and parish leadership.

So there you have at least ten models and precedents. Perhaps they are not all equally fruitful. Nor do all of them operate at the same level. If anything, one of the challenges I am trying to address is the very disparity that leaves some unheralded Christians to improvise patterns of double belonging amid warnings that they are breaking the rules, while warm and generous relationships develop, for example, between Vatican officials and the leadership of Taizé.

Nonetheless, even those precedents that are least accessible to Catholic Mennonites, such as official recognition of non-Roman rites or lay associations of the faithful, remind us that when Romewants to reconcile with a long-estranged Christian community or recognize a movement of the Spirit emerging “from below,” it finds a way. Likewise, when Mennonites want to cooperate with Christians of other churches whom Mennonite historiography or theology once labeled “fallen,” or when Mennonites’ own denominational structures fail to match their lived relationships, they find work-arounds.

Now, I have no idea when, if ever, Mennonites as a community will consider moving toward visible unity with the Catholic Church. Mennonite World Conference leaders are on record assuring doubtful constituents that this is not the purpose of its dialogue with the Vatican. Realistically, I am sure that the only possible purpose of the dialogue at this point is simply to reduce mistrust. And yet anyone who joins in lamenting the scandal of Christian disunity in the face of Jesus’ prayer “that all may be one” is of necessity looking toward a day when matters will be otherwise.

My suggestion is this: If and whenever such a day comes closer, it could actually be easier for Mennonites and some other “free churches” to move toward visible unity than for churches of the magisterial Reformation. Such a claim will no doubt seem counterintuitive to those who assume that the radical Reformation constituted a double estrangement — first from Rome and then from Luther or Calvin. Historians and theologians have been rebutting this for at least three decades by noting certain ways in which Anabaptists remained more Catholic than Protestant in both doctrine and practice.[16] But a further point needs attention, this time with regard to polity:

The greater asymmetry between so-called high and low churches could actually be an advantage. The magisterial Reformation contested Roman claims of apostolic succession in various ways, of course, but did so in part by pitting another hierarchical authority over against that of bishop and pope — namely the prince or city council. The resulting principle, cuios regio eius religio or the regent’s religion is the region’s religion, was if anything hyper-Constantinian. There had been a territorial element Christianity since Saint Paul wrote letters to churches in specific regions and the seer of Patmos wrote to their “angels,” but even after Constantine, ecclesiastical jurisdiction had not necessarily been a zero-sum game. Just as feudalism, whatever its flaws, involved more fluid, overlapping, and federated jurisdiction than would soon be the case within the nation-state system, so too medieval Catholicism allowed bishops and monasteries and then itinerant religious orders all to operate at different levels in the same territory.

With the disestablishment of all churches in North America and of many others elsewhere, we have moved into yet another cultural and political context, of course. But here is a way to notice the continuing legacy of zero-sum territorial ecclesiology: Someone who called herself both Lutheran and Catholic would sound like an unlikely oxymoron, even on this side of the 1999 concord on justification. Someone who called himself both Mennonite and Lutheran would sound like he’s on a post-modern journey. But someone who is both a Franciscan and a Catholic would be altogether unremarkable.

So what about Mennonite Catholics? There is a reason why this does not need to be either impossible or merely postmodern — a reason why one day it could even become unremarkable. Mennonites insist on the need for Christian faith to express itself in communities of local accountability. Catholics insist on the need for every local expression of Christian faith to be accountable to apostolic tradition and to the global Church by way of affiliation with its visible representatives. But these two claims can in principle be complementary rather than competing. For the two foci work at different levels and do not necessarily compete for the same territory.

In fact, many of the precedents I have listed are already beginning to take contemporary expression.

- At a personal level, I already find that the easiest way for me to explain how I can be a Mennonite Catholic is to say I am both in much the same way that a Franciscan or a Benedictine is both.

- At a local level, Bridgefolk groups are emerging in a few locales in ways that are sociologically akin to base communities.

- At a wider level, Bridgefolk as a whole probably qualifies already as an ecclesial movement.

- If an entire Mennonite congregation were to seek entrance into Catholic communion,[17] it seems plausible to expect it could work out a juridical relationship with its bishop roughly analogous to that of a Benedictine monastery.

- And meanwhile, as I have already noted, Taizé seems to be in the process of becoming a de facto Protestant Catholic rite.

Conclusion: Bro. Roger

But perhaps someone has wondered why I keep mentioning Taizé. To be sure, the music of the Taizé community has quickly found a beloved place in Mennonite hymnody, while individual Mennonites have found visits to the Taizé community deeply transformative. But admittedly, Mennonites have no special role or connection with Taizé.

Or perhaps someone else will object that my call for some way to formally recognize patterns of accountable double belonging invites an open season of ecclesial poaching. Rightly, one of Cardinal Kasper’s biggest stated worries about responding to “individual groupings” who knock on his door seeking dialogue outside of official denominational channels is precisely this. “It is a delicate issue,” he has said. “Obviously we do not wish to be involved in any dishonest double-dealing; we want to have absolutely nothing to do with any form of proselytism” and must always respond with “a high degree of transparency toward our partners in other churches.”[18]

So why mention Taizé? Because it not only represents one of the most hopeful signs of Vatican openness to fresh and creative models, it also suggests exactly how to avoid ecclesial poaching.Vatican recognition of Taizé as a Protestant “rite” may only be quasi and de facto at this point. But it is far enough along for us to see the potential of allowing individual Christians and grassroots groups to practice double belonging in accountable ways – precluding mere “cafeteria” grazing by individuals on the one hand, and distancing church policy from ecclesial poaching on the other hand.

It turns out that when Taizé’s aging leader Brother Roger received communion from soon-to-be Pope Benedict XVI at the funeral of John Paul II, it was neither his first Roman Catholic Eucharist, nor was it merely a concession to a wheelchair-bound nonagenarian with an irresistible smile. A few months after the papal funeral, Brother Roger also died in a senseless public stabbing by a mentally ill woman visiting Taizé; a year later, stories began to emerge that way back in 1972, Brother Roger had actually “converted” to Catholicism. The claim was misleading, as the community quickly clarified:[19]

If “conversion” meant renouncing his Protestant origins, no, Brother Roger had not converted, and those who interpreted his journey this way had not “grasped the originality of Brother Roger’s search.” Yes, however, Brother Roger had first received communion in 1972 from the then-Bishop of Autun, Mgr. Armand LeBourgeois, upon his profession of faith according to the Creed. “From a Protestant background,” explained his community, “Brother Roger undertook a step that was without precedent since the Reformation: entering progressively into a full communion with the faith of the Catholic Church without a ‘conversion’ that would imply a break with his origins.”[20]

The journey was anything but private. In 1980 Brother Roger explained it at a meeting in St. Peter’s Basilica, no less, in the presence of Pope John Paul II: “I have found my own identity as a Christian by reconciling within myself the faith of my origins with the mystery of the Catholic faith, without breaking fellowship with anyone.” As his successor Brother Alois has explained: “He was not interested in an individual solution for reconciliation but, through many tentative steps, he sought [a] way [that] could be accessible for others.”

Some of those others are some of us. Personally, I found it little short of astounding to learn these details about Brother Roger. For since my confirmation as a Catholic at Pentecost 2004 I had resisted the label “convert” and instead explained myself in words that are a close theological match to his: “I am a Mennonite who has come into full communion with the Catholic Church.” But although I cannot speak for everyone in Bridgefolk, my deepest hope is for a day when such strictly individual self-definitions and solutions will not be necessary at all.

Surely this too was the hope of soon-to-be Pope Benedict XVI when he offered Brother Roger the Eucharistic host before a watching world, knowing that he was sending a signal, given that few others knew that the Taizé leader had come into full communion years before, but in an unconventional way. Surely this too was the hope of Cardinal Walter Kasper when he officiated at Brother Roger’s funeral mass. For in a church so ritually attuned as the Catholic Church, these are not just expressions of hope but signals calling forth hope.

And in Christianity, hope takes on flesh.

Enfleshed, scarred, but thus healing and still itching, yes, we do go knocking at doors.

Notes

[1]. In speaking of “the bridging of folk” or “bridge people,” I am referring not just to participants in the Bridgefolk movement or organization, but to others like them as well, who seek to bridge multiple traditions.

[2]. Walter Cardinal Kasper, “Current Problems in Ecumenical Theology,” Reflections 6 (Spring 2003): 64–65; Joseph Ratzinger, Church, Ecumenism, and Politics: New Essays in Ecclesiology (New York: Crossroad, 1988), 87.

[3]. Giuseppe Alberigo, ed., History of Vatican II, 5 volumes, English version edited by Joseph Komonchak (Maryknoll, NY; Leuven, Belgium: Orbis Books; Peeters, 1996), I:2–3.

[4]. Pope John XXIII, Gaudet mater ecclesia, Opening speech to the Second Vatican Council (1962).

[5]. The Mennonite-Catholic dialogue also gave some attention to ecclesiology and sacraments or ordinances, though in my judgment with less creativity. And there are certainly Mennonites for whom the papacy or Mariology is an obstacle, or who assume that Catholics believe in justification through works — just as there are Catholics who will wonder how far Mennonite/Catholic dialogue can proceed until Mennonites recognize thecharism of office as realized through the sacrament of holy orders.

[6]. Pentecostals and Baptists have discussed with Catholics the role of Mary in God’s economy of salvation. Anglicans and Eastern Orthodox know they can never recover formal unity with the Roman church until they come to terms on the Petrine ministry of the bishop of Rome. The Faith and Order process mainly among Protestant churches has taken on a host of issues through the years but the title of a 1982 watershed document names the most important — “Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry” (World Council of Churches, Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry, adopted by Faith and Order at its plenary commission meeting in Lima, Peru in 1982, Faith and Order Paper, no. 111 [Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1982]). And of course we can all be grateful for the breakthrough achieved in 1999 with the concord between Lutherans and Catholics concerning justification by grace through faith. The World Methodist Conference has incidentally illustrated my point here by officially signing on to the Lutheran-Catholic concord.

[7]. But note also the perspective of Bro. Roger of the Taizé community in France: “Over the years, the ecumenical vocation has fostered an invaluable exchange of views. This dialogue constitutes the first-fruits of reconciliation. But when the ecumenical vocation is not made concrete through a communion, it leads nowhere.” Glimmers of Happiness (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2007), 90.

[8]. See for example John Howard Yoder, “On Christian Unity: The Way from Below,” Pro Ecclesia 9, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 165–83.

[9]. Perhaps word “Constantinian” is too loaded, since some will reply that the authority of church officials to negotiate on behalf of their communities owes nothing to political authorities (now, anyway) and everything to the apostolic mandate that has constituted an authoritative magisterium in Christ’s Church. But such a reply only underscores Yoder’s point: A key ecclesiological point is being begged. That is, the very position that needs proving is serving as the premise of the argument.

[10]. I am alluding here to Yoder’s interpretation of Ephesians 4:7-13, which provided the overarching image and title for Yoder’s argument that all Christians share in the church’s mission, John Howard Yoder, The Fullness of Christ: Paul’s Revolutionary Vision of Universal Ministry (Elgin, Ill.: Brethren Press, 1987).

[11]. Thus, even those of us who fully accept the Trinitarian structure of Nicaea and Chalcedon as an irreplaceable framework for Christian unity have reason to wonder: Why have Johannine formulae such as “I and my Father are one” or “whoever sees me sees the one who sent me” underwritten the metaphysics of the creeds but failed to underscore, historically, a nonviolent ethic of discipleship? After all, when Jesus himself spoke most explicitly of his Father’s character, pointing out that God makes rain to fall on just and unjust alike, this served to underscore that we too must love our enemies and respond to their aggression with creative nonviolence. So too, one would think that the more Christians agree on the saving power of Jesus’ cross and resurrection, the more they would see that Christ-like suffering service on behalf of others is the true power that truly secures our lives even now in history, not domineering violence.

[12]. Again, one may cite Bro. Roger of Taizé: “A significant step will have been accomplished to the extent that a life of communion, already a reality in certain places throughout the world, is explicitly taken into account. It will require courage to recognize this and draw the necessary conclusions. Written documents will come later. Does not putting the accent on written documents cause us in the end to lose sight of the Gospel’s call to be reconciled without delay?” Glimmers of Happiness, 91.

[13]. Walter Kasper, Cardinal, “The Current Ecumenical Transition,” Origins 36, no. 26 (7 December 2006): 411–13.

[14]. Kasper, “The Current Ecumenical Transition,” 412–13.

[15]. Gerald W. Schlabach, “The Vow of Stability: A Premodern Way Through a Hypermodern World,” in Anabaptists & Postmodernity, eds Susan Biesecker-Mast and Gerald Biesecker-Mast, foreword by J. Denny Weaver, The C. Henry Smith Series, vol. 1 (Telford Pa.: Pandora Books U.S., 2000), 301–24; Gerald W. Schlabach, “Stability Amid Mobility: The Oblate’s Challenge and Witness,” American Benedictine Review 52, no. 1 (March 2001): 3–23.

[16]. Ground-breaking in this regard was Walter Klaassen, Anabaptism: Neither Catholic Nor Protestant (Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Conrad Press, 1981); Klaassen reportedly remarked later that he wished he had named the book “Anabaptism: Both Catholic and Protestant.”

[17]. I know the leaders of one Mennonite congregation have at least played with this idea.

[18]. Kasper, “The Current Ecumenical Transition,” 413.

[19]. The report first emerged in the newsletter of a traditionalist Catholic organization, and was picked up by the French daily Le Monde in an article of 6 September 2006. The Taizé community’s clarification is available at http://www.taize.fr/en_article3864.html, with links to related documents.

[20]. Bro. Roger had explained at greater length in Glimmers of Happiness, 92–93:

After the First World War, [my maternal grandmother’s] deepest desire was that no one should ever have to go through what she had gone through. Since Christians had been waging war against each other in Europe, she thought, let them at least be reconciled to prevent another war. She came from an old Protestant family, but, living out an inner reconciliation, she began to go to the Catholic Church without making any break with her own people.

Impressed by the testimony of her life when I was still fairly young, I found my own Christian identity by reconciling within myself the faith of my origins with the mystery of the Catholic faith without breaking fellowship with anyone.